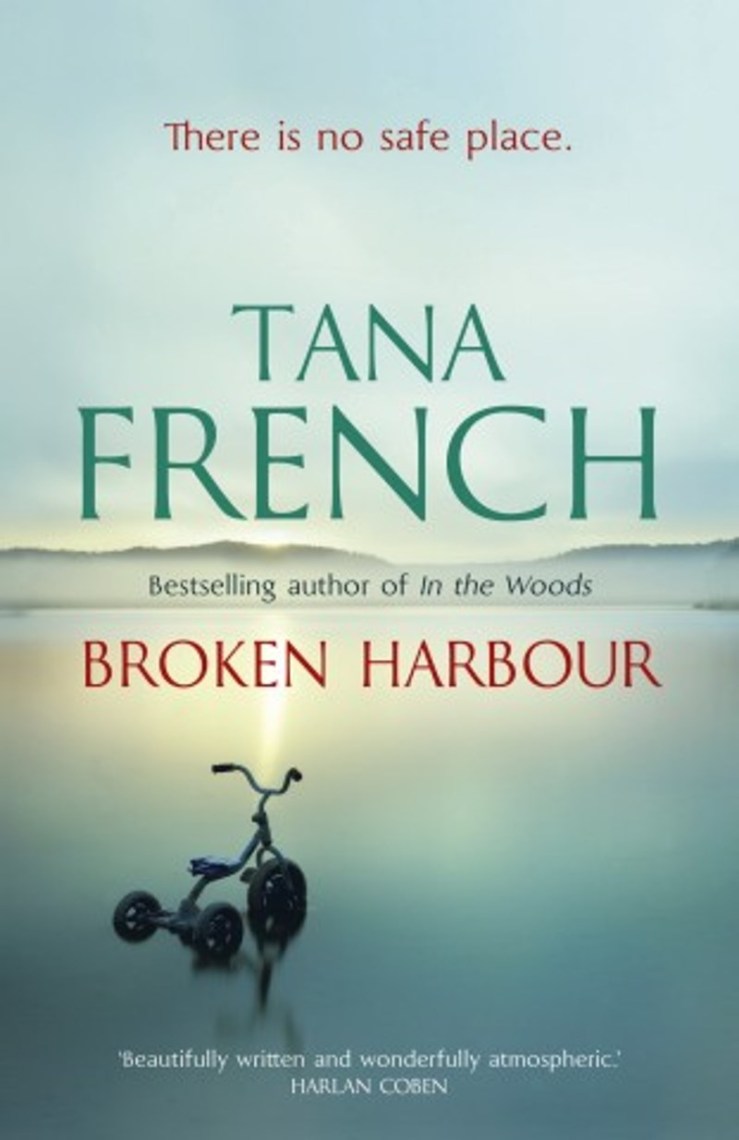

Recipe for a Tana French Dublin Murder Squad novel:

Take an atmospheric and intense setting, such as the last remnant of an ancient forest, a secluded mansion or a half completed housing project abutting the sea; insert a handful of characters with intense and golden relationships; raise the pressure and temperature; remove from the oven when those relationships start to rip slowly and tortuously apart; dust with a subtle hint of the supernatural.

This is the fourth of Tana French’s explorations of the fictional Dublin Murder Squad, after In The Woods, The Likeness and Faithful Place. I first read The Secret Place and loved it enough to gorge on the rest of the series which I continued to love – although Faithful Place has been a struggle to get into. This entry, however, I think is the strongest in the series so far.

The setting, the characters, the language here are all pitch-perfect: heightened but utterly convincing; rooted in the economic reality of the recession in Ireland but with a poetic lyricism. The Spain family is found slaughtered in their safe and middle class home in a housing project which was abandoned as the investments ran out surrounded by shells of houses and ghosts of what could have been: their children had been smothered; the father, Pat, knifed to death; the mother, Jenny, barely alive. An experienced detective, Mick “Scorcher” Kennedy – being offered a chance to reclaim past glory following some vaguely hinted at disaster – is paired with a rookie detective to investigate. As usual with French, the relationship between the detectives and the budding trust and respect between Kennedy and Richie Curran – a mentor-mentee relationship growing into a putative partnership – is a beautiful and tender as the victims’ relationships. Kennedy is not immediately likeable saying such things as

“in this job everything matters, down to the way you open your car door. Long before I say Word One to a witness, or a suspect, he needs to know that Mick Kennedy is in the house and that I’ve got this case by the balls. Some of it is luck—I’ve got height, I’ve got a full head of hair and it’s still ninety-nine percent dark brown, I’ve got decent looks if I say so myself, and all those things help—but I’ve put practice and treadmill time into the rest. I kept up my speed till the last second, braked hard, swung myself and my briefcase out of the car in one smooth move and headed for the house at a swift, efficient pace. Richie would learn to keep up.

But a softer side to him emerges, whether it be consoling Curran in the autopsy or keeping his sister, Dina, whose mental state is simultaneously vulnerable and perceptive, safe or in his own deeply tragic personal history. He is a man who presents a mask to the world and may not know himself where the real face lies beneath it.

In terms of the plot, French keeps up a cracking pace: the advantage of the detective fiction form, perhaps. Pat, the dead father, is initially suspected; a stalker is discovered quickly but the case keeps deepening.

French’s prose, in the lips of different protagonists in each novel, is, as always, beautiful, poised between the lyrical and the real. As he enters the house, Kennedy tells us

that was when I felt it: that needle-fine vibration, starting in my temples and moving down the bones into my eardrums. Some detectives feel it in the backs of their necks, some get it in the hair on their arms—I know one poor sap who gets it in the bladder, which can be inconvenient—but all the good ones feel it somewhere. It gets me in the skull bones. Call it what you want—social deviance, psychological disturbance, the animal within, evil if you believe in that: it’s the thing we spend our lives chasing. All the training in the world won’t give you that warning when it comes close.

And when he sees the harbour, where his own personal tragedy is centred, we are told of the

rounded curve of the bay, neat as the C of your hand; the low hills cupping it at each end; the soft gray sand, the marram grass bending away from the clean wind, the little birds scattered along the waterline. And the sea, high today, raising itself up at me green and muscled. The weight of what was in the kitchen with us tilted the world, sent the water rocking upwards like it was going to come crashing through all that bright glass.

And, finally, when looking into the Spains’ attic, an attic guarded with a thick mesh and holding a vicious bear trap, Kennedy says that

For an instant I thought I saw something move—a shifting and coalescing of the black, a deliberate muscled ripple—but when I blinked, there was only darkness and the flood of cold air.

As well as location and atmosphere, which she manages and manipulates with an exquisite Gothic sensibility, French is very good at insanity here. No spoilers, but the Spains, behind their own affluent and successful mask – which marks them out as snobs to their few neighbours – both disappear into different rabbit holes. And they are both wholly credibly described and experienced by the reader.

This is one of the best detective novels I have ever read. Full stop. It is literary and eloquent but never loses its way as a piece of detective fiction. And its conclusion and final revelation – and the ethical dilemmas explored – are enough to warrant tears. Hauntingly, chillingly beautiful.

[…] The Secret Place and going back to start her Dublin Murder Squad series from the start – Broken Harbour is in my opinion the best. She has a great sense of close, intimate relationships and a Gothic […]

LikeLike

[…] relationships have developed: we’ve met “Scorcher” Kennedy who narrated Broken Harbour – and learnt the origin of that nickname; and we’ve just been introduced to Stephen […]

LikeLike

[…] more fully to the Murder Squad detectives ‘Scorcher’ Kennedy and Stephen Moran in Broken Harbour and The Secret Place respectively. Both these detectives have cameos in Faithful Place and it felt […]

LikeLike

[…] Gothic sensibility which sets it apart from other series. And the entry which best encapsulates it? Broken Harbour, which revolves around a family being murdered in an half completed housing complex, which may or […]

LikeLike

[…] where mysterious affairs happen, the Nile which sees death, or Tana French’s Faithful Place, Broken Harbour or The Secret Place. When you come across a blunt title like Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot […]

LikeLike

[…] I managed to bookend the year with Gothic readings! I entered 2018 reading Broken Harbour, a fabulous entry into the Dublin Murder Squad series by Tana French, and having a deeply Gothic […]

LikeLike

[…] least this entry in the series) is a fabulous achievement of it! Atkinson and Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad series are both […]

LikeLike

[…] favourites in the series are probably The Likeness for its intense relationships and Broken Harbour for its depiction of madness, insanity and perhaps the possibility of something real hiding within […]

LikeLike

[…] on creating a reliable narrative of the crimes that took place! My favourite is without a doubt Broken Harbour with a wonderful depiction of the mental breakdown of an entire […]

LikeLike

[…] – and more often difficult ones such as Scorcher Kennedy and Dina in Tana French’s Broken Harbour. But these are more directly focused on those sibling […]

LikeLike

[…] reliable or stable. Gothic, unnerving and tense, these are incredible novels. And my favourite? Broken Harbour without a doubt: the beast hiding in the walls of the house is almost out of a Gaiman […]

LikeLike

[…] of fairly unreliable narrators from Rob in your first novel, In the Woods to Scorcher Kennedy in Broken Harbour. Allied to that, truth and justice seem very slippery concepts in your novels and your resolutions […]

LikeLike

[…] been haunted by a goat-smelling presence, or perhaps the muscular darkness lurking in the attic of Broken Harbour. And it was wonderful seeing Cal seduced by the possibility of something other as an explanation […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Broken Harbour, Tana French […]

LikeLike

[…] Broken Harbour, Tana French […]

LikeLike

[…] far away, whether it be beasts in the woods, ghosts and magic, or – as in my favourite novel, Broken Harbour – a creature in the walls of your […]

LikeLike

[…] Broken Harbour, Tana French – The Dublin Murder Squad series […]

LikeLike

[…] that the Tana French novels feature a taste of the Gothic which comes to the fore mostly in Broken Harbour for me where a family become obsessed that a beast of some kind is living within the walls of their […]

LikeLike

[…] Broken Harbour, Tana French […]

LikeLike