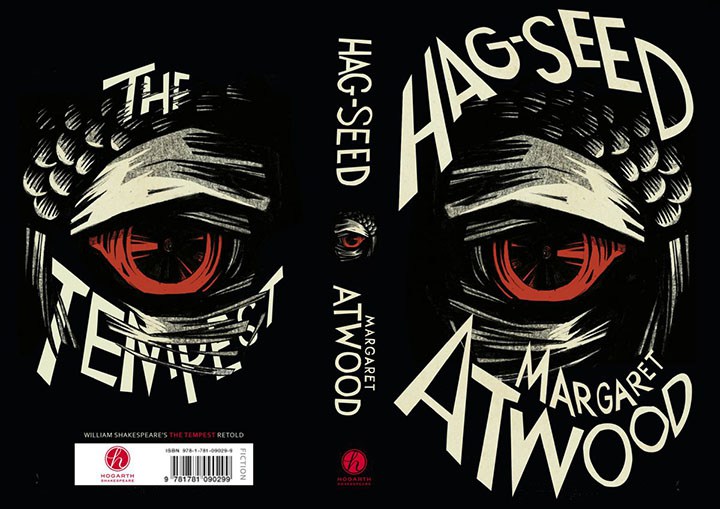

Once again, a deliciously striking cover for Margaret Atwood’s most recent novel, and the most recent entry into the Hogarth Shakespeare Project… and the first in the project that I’ve read.

Now, I have a confession to make before going much further: I’ve never really got Margaret Atwood. I’ve wanted to; I’ve tried to. I really have. The Handmaid’s Tale, Oryx and Crake, The Blind Assassin, The Heart Goes Last… I’ve found them all daunting and I’m not usually daunted by books. Maybe daunting isn’t the right work. I’ve just never got into them however hard I’ve tried.

But this one, I actually really loved!

A re-invention of The Tempest, Hag-Seed is set in Makeshiweg, Canada where Prospero is re-imagined as Felix, the director of a local theatre festival, usurped by the Machiavellian machinations of a deliciously corporate Tony, an act which similarly de-rails his plans for a production of The Tempest. And within that circularity is encapsulated a taste of the delightful self-referentiality of the novel: theatres and productions and prisons and revisions and re-versions of the play multiply dizzyingly. Felix seemed perpetually with one-foot in the play: even before the villainous firing, he had lost his wife and named his daughter Miranda.

And Miranda is the heart of this novel: unlike Prospero’s daughter, Felix lost his own child and conjures her up as a memory which elides into an hallucination and slips into ghostliness through the novel. Simultaneously present and absent. Desperately clung to by Felix. Student and teacher.

Despite the ridiculous over-the-top caricature which Felix can become

His Ariel, he’d decided, would be played by a transvestite on stilts who’d transform into a giant firefly at significant moments. His Caliban would be a scabby street person – black or maybe Native – and a paraplegic as well, pushing himself around the stage on an oversized skateboard.

Atwood truly creates empathy and real pain in his oh-too-real experience of his grief as a father. At times, it feels touched by Hamlet rather than just The Tempest.

Felix slinks into a self-imposed exile following his firing and spends twelve years following the evil Tony’s rise to government and slowly plotting his revenge, a revenge which requires the Fletcher Correctional Facility to achieve via a Shakespeare Literacy Programme in which the inmates perform a Shakespeare play each year. As Tony and his cronies circulate and plan to visit Fletcher, Felix uses The Tempest as a tool with which to exact his revenge in a dark and drug-fuelled finale.

Personally, I preferred the build-up and rehearsal to the actual performance of the play and the enactment of the revenge. I loved the way that the inmates who were Felix’s cast toned down the self-indulgent theatricality of his original ideas and added rap, cynicism, kitsch and machismo to his re-invented re-invention. The actress Anne-Marie – a feisty and cool kick-ass dancer who can hold her own in the prison – becomes his Miranda; his Miranda becomes his Ariel.

At heart, the novel is an achingly painful and beautiful farewell from a father to his memories of his daughter and an ownership of grief. The final farewell genuinely brought tears to the eyes.

Other entries to the Hogarth Shakespeare Project include Jeanette Winterson’s The Gap of Time (The Winter’s Tale), Howard Jacobson’s Shylock Is My Name (The Merchant of Venice) and Anne Tyler’s Vinegar Girl (The Taming of the Shrew). I look forward to picking these up and, when they’re released, Tracy Chevalier’s Othello, Gillian Flynn’s Hamlet, Jo Nesbo’s Macbeth and Edward St Aubyn’s King Lear to come.

[…] it is part of the Hogarth Shakespeare series, which are usually reliable alongside Howard Jacobson, Margaret Atwood, Tracy Chevalier… And whilst the Harry Hole series were a little Scandi-noir for my taste, […]

LikeLike