“Rain was the natural state of Glasgow. It kept the grass green and the people pale and bronchial.”

I have been delaying reviewing this book for a while, wanting to let it dwell in my mind for some time before putting my thoughts down… and then life got in the way – as did new books – and I ended up leaving it on the back burner for far too long!

Synopsis

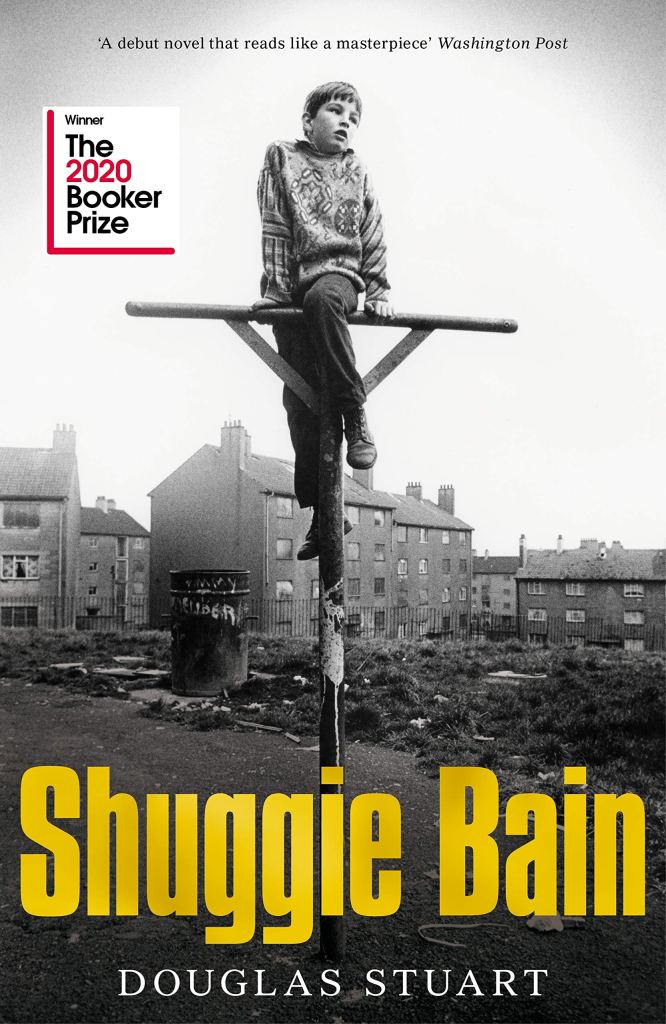

It is 1981. Glasgow is dying and good families must grift to survive. Agnes Bain has always expected more from life. She dreams of greater things: a house with its own front door and a life bought and paid for outright (like her perfect, but false, teeth). But Agnes is abandoned by her philandering husband, and soon she and her three children find themselves trapped in a decimated mining town. As she descends deeper into drink, the children try their best to save her, yet one by one they must abandon her to save themselves. It is her son Shuggie who holds out hope the longest.

Shuggie is different. Fastidious and fussy, he shares his mother’s sense of snobbish propriety. The miners’ children pick on him and adults condemn him as no’ right. But Shuggie believes that if he tries his hardest, he can be normal like the other boys and help his mother escape this hopeless place.

Amazon.co.uk

Thoughts

Firstly, this book won practically everything going last year – well, The Booker Prize, ‘Book of the Year’and ‘Debut of the Year’ at the British Book Awards 2021 – and was nominated for a clutch more and quite rightly so.

It is a devastating yet tender, brutal yet delicate depiction of life in working class Glasgow and it focuses on Hugh “Shuggie” Bain’s mother, Agnes – oddly the second utterly compelling character named Agnes from 2020 after the sublime Agnes in Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet. Rather than the folkloric, elfin, otherworldly Agnes in O’Farrell, Stuart’s Agnes is broken from the first time we see her.

That first opening image (apologies for the length of the ensuing quotation) literally places Agnes on a tipping point and it feels that she remains teetering on that precipice for the rest of the novel

Agnes Bain pushed her toes into the carpet and leaned out as far as she could into the night air. The damp wind kissed her flushed neck and pushed down inside her dress. It felt like a stranger’s hand, a sign of living, a reminder of life. With a flick she watched her cigarette doubt fall, the glowing embers dancing sixteen floors down on to the dark forecourt. She wanted to show the city this claret velvet dress. She wanted to feel a little envy from strangers, to dance with men who held her proud and close. Mostly she wanted to take a good drink, to live a little.

With a stretch of her calves, she leaned her hipbone on the window frame and let go of the ballast of her toes. Her body tipped down towards the amber city lights, and her cheeks flushed with blood. She reached her arms out to the lights, and for a brief moment she was flying.

No one noticed the flying woman.

She thought about tilting further then, dared herself to do it. How easy it would be to kid herself that she was flying, until it became only falling and she broke herself on the concrete below.

I adore this opening image: it is so brilliant an encapsulation of her character! Her desire for passion and romance (the wind “kissed” her “flushed neck” and the embers of her cigarette were “dancing”) and sexual excitement (the wind “pushed down inside her dress… like a stranger’s hand”) and to “life a little”. At the same time, there is a palpable sense of her being trapped. Trapped by the window frame, by her parents’ flat in which she lives with her violent and philandering husband, and her three children – “two of them nearly grown” – by the society of her mother’s friends Nan Flannigan and Reeny Sweeney who call her back to their card games and catalogues.

Nothing about Stuart’s language is wasteful, nothing is forced into an uncomfortable poetry or lyricism. There is a brutal and muscular honesty about it in the descriptions of the enclosed stuffy flat, in the dialogue which is coarse and unvarnished, in the depiction of Agnes’ descent into alcoholism.

And Agnes does descend and descend oh so hard!

Initially, her husband, Hugh “Big Shug” Bain, appears to help her escape her parents’ flat in Sighthill by finding a house in Pithead which might be

only a wee place, but it’s got its own garden and its own front door and everything.

And isn’t that modest ambition, to have your “own front door” so beautifully deployed.

Everything looks rosy – which soon seems a dangerous thing in this novel, Stuart likes to give glimmers of hope he later rips away – with a new start together as a family but then, having dropped them off, Big Shug never brings his own bags in. Instead, he abandons Agnes to her new house as a single mum whilst he disappears off to live with Joanie Micklethwaite, the dispatcher from his taxi company. The only recourse available to Agnes was alcohol, and she clung to it with a fierceness which ignored everyone else around her.

The depiction of alcoholism – and the effect on Agnes of alcoholism – was utterly convincing and authentic from the hidden cans of special brew, to the desperate visits to the pawnbroker, to the nights passed out drooling on the sofa, to the depredations inflicted on her by men. It was brutal and unremittingly bleak and this was not an easy read at all dealing with sexual assault and Agnes’ multiple suicide attempts in horrifying detail.

Yet it was always redeemed by Agnes’ own indomitable pride and insistence on having manners and cleanliness and being well presented in her self and in her house. And there was a real and genuine heroism in that. There was one beautiful moment when Shuggie is dancing for his mother in their front room – and Stuart is great with the power of that image of dancing throughout the novel and all the glamour that it promises – and the neighbours bullying jeering children spot him.

Without looking out the window she spoke through clenched teeth. “If I were you, I would keep dancing.”

“I can’t.” The tears were coming.

“You know they only win if you let them.”

“I can’t.” His arms and fingers were still outstretched and frozen, like a dead tree.

“Don’t give them the satisfaction.”

“Mammy, help. I can’t.”

“Yes. You. Can.” She was still smiling through her open teeth. “Just hold your head up high and Gie. It. Laldy.”

Inevitably those few pillars of support Agnes has in her children Catherine and Alexander or “Leek” topple or are pushed away by Agnes herself as Catherine marries and flees to South Africa, and Leek is kicked out after a bitter argument, leaving Shuggie to look after his mother alone.

And that bond of love between Shuggie and his mother, initially blind and uncomprehending of his mother’s addiction, but increasingly aware and conscious as he grows, is so incredibly warm and heartfelt.

Agnes does, at one point, accept her problems and reaches out to Alcoholics Anonymous, and the depiction of that and of her struggle to remain sober was again utterly convincing. And had me on the edge of my seat because it occurred only about half way through the novel and I was just waiting for the inevitable relapse to come, even as Agnes began a new job, found a new man in Eugene, made new friends from her meetings and re-bonded with both Leek and Shuggie…

The conclusion of the novel was perhaps inevitable from its opening pages, but Stuart created it so beautifully and so tenderly without losing any of the honesty that it genuinely did move me to tears.

Thus far we have barely mentioned the titular Shuggie whose journey from child to young man is at the heart of the novel. His depiction as a child who is seen as different – often seen as effeminate, camp and a “poofy little fairy”; possibly, in his fastidiousness, somewhere on the autistic spectrum; a caregiver for his mother – is deeply affecting as he is bullied at school, unable to maintain the occasional friendships that he does form, is neglected by Agnes and taken advantage of by boys and men. He opens and closes the novel when, living alone at 15 in 1992, he is in a boarding house with ambitions of becoming a hairdresser. And despite everything he has survived, he is still able to dress up in “poncey school shoes” and with his friend Leanne he can still dream of dancing and ends the novel as he “nodded, all gallus, and spun, just the once, on his polished heels”.

A beautiful poignant final image.

What I Liked

- The wonderful, honesty of Stuart’s language in which every word, phrase and image was simultaneously utterly credible and carefully crafted to be replete with meaning.

- Agnes – for all her many many flaws she was incredibly brave and somehow, even, heroic in her own right.

- The wonderful characterisation, not simply of the main characters, but also the wide supporting cast of Agnes’ neighbours in Pithead, where everyone in the community was sympathetic and fully realised even if they only floated into the pages of the novel for a few pages.

- Eugene – not for himself but for the way that Stuart used him within the narrative. Extremely well crafted.

What I Disliked

- I’m going to be honest… I am not sure whether there was anything I disliked about this novel! It was bleak without being hopeless; it explored the redemptive power of love without ever becoming sentimental. It was sublime.

Overall:

Characters:

Plot / Pace:

Worldbuilding:

Structure:

Language:

Page Count: 448 pages

Publisher: Picador (Pan MacMillan)

Date: 6th August 2020

[…] Shuggie Bain, Shuggie Bain […]

LikeLike

[…] Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart […]

LikeLike

[…] Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart […]

LikeLike

[…] Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart […]

LikeLike