Authenticity is often what we look for in a book. Is the setting authentic? Are my characters authentic? Is my voice authentic? Is my lexis authentic? It doesn’t take much sometimes to pull a reader from a novel and inauthenticity can do it. I’ve still got concerns about the use of the f-word in Hilary Mantel’s glorious Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies. Some writers embrace otherness and the inauthentic to create something lyrical and beautiful. Others like Jim Crace’s Harvest and Gift Of Stones are credible and authentic but we never lose track of the fact that these are novels.

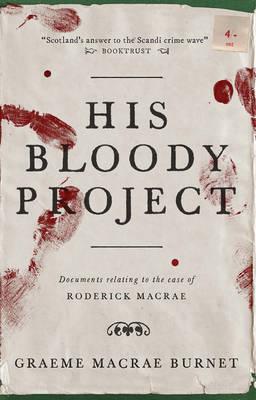

Gramme Macrae Burnet goes the other way: His Bloody Project drips with authenticity to the point where it blurs the boundaries of fiction and history. Purporting to be a collection of found historical documents, found when

“In the spring of 2014 I embarked on a project to find out a little about my grandfather, Donald ‘Trump’ Macrae, who was born in 1890 in Applecross…”

In addition to this preface, Burnet embeds his novel in reality: the villages of Applecross and Culduie are real; the criminologist James Bruce Thomson is real; the grim and ungenerous land is real; the daily trials and hard work required to eke a living from that land is utterly credible and authentic. The temptation is to accept the historical authenticity as fact, to turn to Google or Wikipedia to discover which characters are actually real!

On 12th April 1869, Roderick Macrae – inhabitant of Culduie in the far reaches of Scotland – killed Lachlan Mackenzie – known as Lachlan Broad. Murdered him and his sister and his infant son. Bludgeoned them with a croman and flaughter. Don’t worry, a glossary is provided in the novel.

No spoilers here: we learn that in the opening pages of this Man Booker shortlisted novel. Unlike most crime fiction (and that – along with other things – is what this is), there is never any doubt as to who committed the crime: Macrae is discovered covered in blood and admitting the deed. It is not so much a whodunit as a whydunit. And perhaps an exploration of how impossible a task it is to know the contents of another man’s heart or mind. Because Macrae’s only defence is his own insanity.

And I’m not sure we ever receive any answer: the witness statements and testimony and expert opinion and especially Macrae’s own purportedly personal account all testify to the impossibility of knowing. They confuse and contradict and complement each other throughout.

There is so much to admire here: the wealth of narrative voices, all of which are again authentic; it’s a compelling exploration of the deprivation of the crofters’ life; it’s an examination of the misery that an abuse of power can create. It is comical in the second half’s account of the trial, and absurd – especially when Macrae’s father visits the factor to discover and inspect the regulations under which his tenancy is governed, having been challenged for breaking them, and is told that

“a person wishing to consult the regulations could only wish to do so in order to test the limits of the misdemeanours he might commit.”

It is a fascinating, although ultimately bleak and harrowing glimpse into history and a thoughtful game between Burnet and the reader exploring that boundary between history and story. And also a cracklingly good read behind the literary mind games.

[…] – The Disappearance of Adele Bedeau by Graeme Macrae Burnett, mainly on the strength of his His Bloody Project book which I found fabulous. Not quite sure of this one yet: a lot of telling rather than showing […]

LikeLike

[…] Macrae Burnet came to my attention through the Booker Prize: I loved his His Bloody Project novel with its multiple voices and setting, evocatively recreating the brutality of life in […]

LikeLike

[…] guilt – that I’ve not chosen The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne. Or His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae […]

LikeLike

[…] His Bloody Project, Graeme Macrae Burnet […]

LikeLike

[…] His Bloody Project, Graeme Macrae Burnet […]

LikeLike

[…] Macrae Burnet returns with a literary mystery that will beguile fans of His Bloody Project and The Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau. Darkly humorous, subtle and sophisticated, The Accident […]

LikeLike

[…] narrative bending style – playing with the idea of found texts, false documents – in His Bloody Project and this looks like more of the […]

LikeLike

[…] many on this list, Macrae Burnet was listed for the Booker and I had loved His Bloody Project. Here, the so-called found novel structure was starting to feel a little overworn perhaps and his […]

LikeLike

[…] Macrae Burnet was the standout narrative voice of the 2016 Booker longlist and shortlist with His Bloody Project: the ‘found’ narrative of a brutal murder in a crofting community showed a wide range […]

LikeLike

[…] Grenville’s grandmother, it was not a fictional construct as in Graeme Macrae Burnet’s His Bloody Project – brought a humanity and intimacy to the novel which its almsot frenetic pace sometimes […]

LikeLike