This is a remarkable novel.

This is a remarkable novel.

Of the three CILIP Carnegie nominees I’ve read, this is my clear front runner. And I’m saying that having read Patrick Ness!

Before I review it, however, I’m going to play a game with my sixteen year-old stepson, whose birthday it is today. Despite his protestations, he is going to give me three numbers between 1 and 408, which is the number of pages in the book. His choices are: 407, 52 and 64. I think that the novel is so rich in (or over-abundant in, depending on your sensibilities) figurative language that I’ll be able to find an example on each page!

Page 407: Trista’s smile is “thorny”, which may be literal or figurative; her life is a “book” which could have been “closed”; the Crescent family is a “jigsaw”.

Page 52: The doctor smiles “warmly” and describes trauma as being like a time when you “swallowed a marble” causing “A … sort of tummy ache of the mind”; an explanation which is “homely”.

Page 64: Triss was driven home “with jazz in her blood” made up of “leaping” melodies; her sense of identity “closed in on her again, like cold, damp swaddling clothes”; a motorbike is described as a “lean, black creature”, out-of-place like “a footprint on an embroidered tablecloth”; it was “bold”, with the “rough cockiness of a stray dog”.

One of the first things that leapt at me from the novel was the level of metaphor, simile, personification and pathetic fallacy. Perhaps it was particularly noticeable having used the word “sparse” to describe the prose in previous recent reads. In fact, it was so noticeable I had blogged about it here. Not quite purple prose but a little self-indulgent perhaps, a little self-aware. Actually, quite close to my own writing style so perhaps I recognised the richness in the same way I’d recognise my own reflection – and that was a very deliberate analogy!

But each simile and metaphor is gorgeous and resonant. I particularly liked the following quote

Outside Triss’ room, the evening came to an end. There was movement on the landing, muffled voices, door percussion. The faint rustles and ticks of the sleep-time rituals. And then, over the next two hours, quiet settled upon the house by infinitesimal degrees, like dust.

The story itself is evocative and powerful. And very British. It revolves around changelings and fairies and elves – but very much in the vein of Shakespeare’s Puck rather than Disney: mischievous, childish, animalistic creatures whose interactions with humanity are nervous, whimsical and suspicious. And it is a crackinglingly good adventure story in its own right.

Set in the aftermath of World War One, it is also a bone-achingly dissection of grief and loss. Not simply at an individual level – Triss’s brother, Sebastian having died in the French trenches – but also at a societal level. The shattering of the pre-war traditions and beliefs and structures; and the futile efforts of some characters to cling to the empty traditions. I can recognise that in my own grandmother’s attempts to maintain the facade of respectability and gentility which did feel like a pantomime – a memory of a ghost of a pantomime – even to my dulled senses.

So how much more appealing is the world of the fairies (or the Besiders) – immigrants forging a life a new life in the cities and towns, fleeing from the countryside and foreign countries. And how apt and poignant is that? As the UK enters a General Election with UKIP currently on 15% of the vote. The Besiders are chaotic, dangerous, afraid; some may be malicious, mostly seeking nothing more than shelter and safety. And in there, perhaps, lies one of the many beauties in the novel: neither the immigrant Besiders not the indigenous humans are demonised. Both communities have suffered; both communities are suspicious of the other; both communities are rich in different ways.

And beneath this again lies a psychological tale of parents and children, the thorny boundaries between love, protection and autonomy being explored in all their complexities and knottiness. Triss’s dependence on her parents, their dependence on her dependence, are dissected with a brutal honesty; sibling rivalries and love grow and rip open characters. How do we forge our identities, our sense of self, when so much of what we are is inherited, borrowed from and imprinted on us by the limited worlds we inhabit. The image of Triss / not-Triss / Trista stuffed full of leaves, twigs and ribbons and borrowed memories is an apt metaphor for each of us struggling to create our own stories, our own voices.

And Violet.

Violet was a wonderful creation: the uncompromising, unsentimental, jazz-feulled motorbiking Violet.

There’s certainly scope in the novel for a sequel – even a series. But I hope Harding doesn’t go down that road. I’d rather have these characters live independently in my imagination, a right that they fought for throughout the novel.

[…] only read this and Cuckoo Song to be fair, but there’s something about her imagination and her writing which chimes with me: […]

LikeLike

[…] Cuckoo Song was a masterpiece. The sort of novel which I wish I had more than my self-imposed five stars to […]

LikeLike

[…] and Brandon Sanderson‘s and Steven Erikson’s epics. Harry Potter. Narnia. Whilst I love Frances Hardinge, I cannot conceive of a way to view her books as a series. Patrick Ness’ Chaos Walking […]

LikeLike

[…] Hardinge’s novels than Ness’. The stand out in Hardinge’s list would have to be Cuckoo Song: deliciously creepy and powerfully written with a lyrical intensity. Talking – screaming […]

LikeLike

[…] pinnacle of her work, for me, has been Cuckoo Song, a novel which I have adored for four years now – was it really 2015 that I first read it […]

LikeLike

[…] 1. Cuckoo Song, Francis Hardinge […]

LikeLike

[…] concerned picking up Deeplight, however much I adore Hardinge because her most recent books from Cuckoo Song and The Lie Tree to A Skinful of Shadows have been deeply rooted in historical settings – in […]

LikeLike

[…] compelling in depth world is exceptional. And Deeplight took us from the historical fantasy of Cuckoo Song, The Lie Tree and A Skinful of Shadows into a fully realised Lovecraftian fantasy world of […]

LikeLike

[…] live Here, Patrick Ness; A Series of Unfortunate Incidents, Lemony Snicket; One, Sarah Crossan; Cuckoo Song, Frances […]

LikeLike

[…] of all of Hardinge, I’d probably recommend either The Lie Tree or Cuckoo Song. They are both tales of young women finding their place in a challenging world: eigthteenth century […]

LikeLike

[…] Cuckoo Song, Frances Hardinge […]

LikeLike

[…] Cuckoo Song, Frances Hardinge […]

LikeLike

[…] and the epitome of the unheimlich. My favourites are essentially neck and neck: The Lie Tree and Cuckoo Song but everything by her is well worth a read for readers of any […]

LikeLike

[…] in her novels, many of which focus on young girls finding their voice and their identity: Triss in Cuckoo Song searching for the truth about herself, Faith in The Lie Tree, trying to juggle the roles of […]

LikeLike

[…] Frances Hardinge […]

LikeLike

[…] Trista, Cuckoo Song […]

LikeLike

[…] Cuckoo Song, Frances Hardinge […]

LikeLike

[…] Cuckoo Song, Frances Hardinge […]

LikeLike

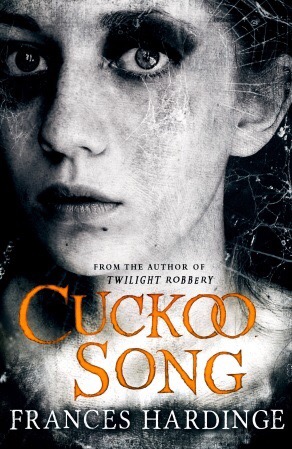

[…] how gorgeous that cover is! There is nothing that Hardinge has written that I have not loved from Cuckoo Song to The Lie Tree to Deeplight, although personally I found the more historical magic realism novels […]

LikeLike

[…] Hardinge is one of those automatic-buy authors for me. Quirky, witty, humane and powerful. Cuckoo Song, The Lie Tree and A Skinful of Shadows were all wonderful! And now we have a new world to discover […]

LikeLike

[…] and readers of this blog that I love Frances Hardinge’s novels – from the historical Cuckoo Song and The Lie Tree to the fantastical Deeplight and A Face Like Glass – and her world building […]

LikeLike

[…] Cuckoo Song, Frances Hardinge […]

LikeLike