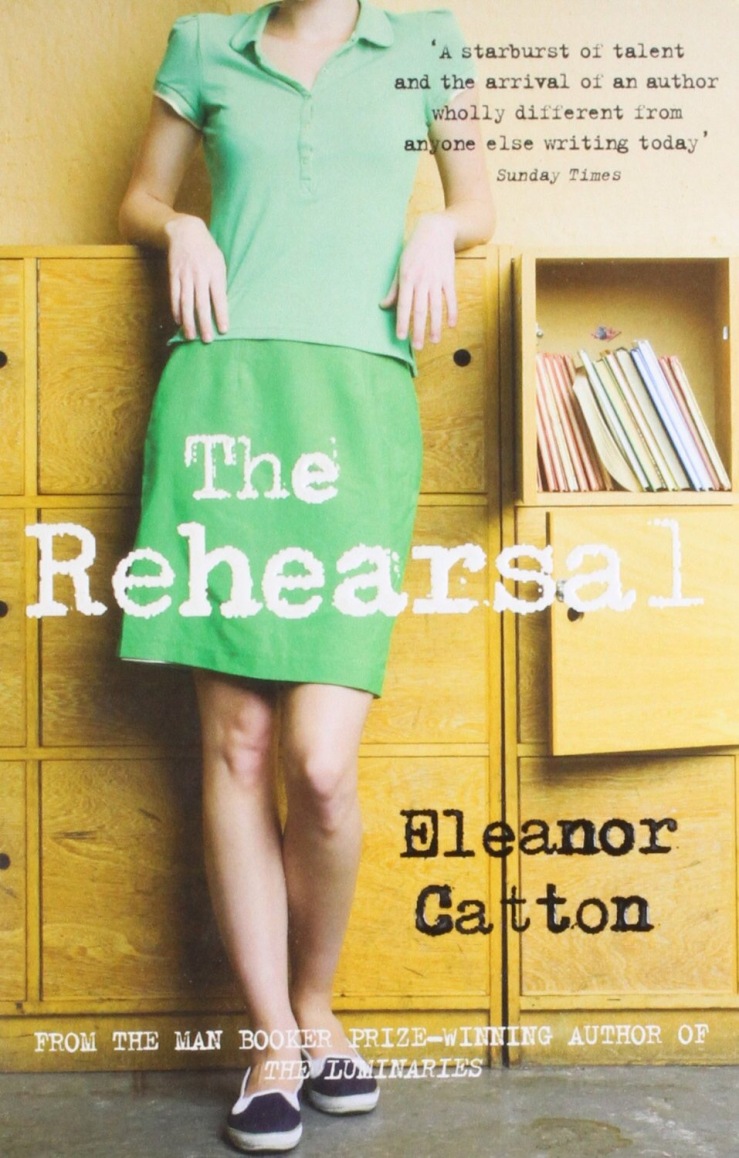

Some books just blow you away.

This one is absolutely in that category. One of those books that I struggle to find an adjective to describe the experience of reading it. Astonishing. Scintillating. Experimental. Complex. Extraordinarily sensuous.

I can understand why many people might not like it. It is written in a non-linear way – using one of its own symbols, that of a shuffled pack of cards. It plays with and explores the whole nature of truth, deception, self-deception and the playing of and creation of roles. Focussing primarily on teenage girls, their self-creation is at the heart of the novel.

The dialogue is, at times, realistic and utterly convincing; at other times, it is deliberately unrealistic and crafted. As an example, this is the Saxophone Teacher’s monologue to a prospective parent:

I require of all my students that they are downy and pubescent, pimpled with sullen mistrust, and boiling away with private fury and ardour and uncertainty and gloom … If I am to teach your daughter, you darling hopeless and inadequate mother, she must be moody and bewildered and awkward and dissatisfied and wrong.

With that ringing in my ears, as a teacher, I realise that I’ve been doing Parents’ Evenings all wrong!

This language is beautiful! Unnatural, poetic and calling attention to itself. But beautiful.

Rather like The Luminaries, the focus Catton has on playing with narrative structures and registers of language could have come across as somewhat self-congratulatory and, let’s face it, pretentious. But it doesn’t come across in that way for me. It is witty, unsettling and refreshing. It is one of those books that I felt giddy reading.

The plot revolves around two creative processes: the saxophone lessons offered by the unnamed Saxophone Teacher to three female students in preparation for a recital; and the local Drama Academy First Year drama performance. What links these two strands together is the revelation and response to a sexual relationship between a male teacher, Mr Saladin, at the local school and one of his female pupils, Victoria. The Saxophone Teacher teaches Isolde, Victoria’s sister – and how telling is it that the first we hear of the relationship is as an excuse for not having practised and Isolde’s obviously rehearsed recitation of it – and the students of the Drama Academy appropriate the story – or a version of it – as the focus of their drama.

Now that relationship in itself is a deeply difficult topic! It would have been easy to be preachy and demonise the teacher – Mr Saladin – as the Daily Mail article attached here does; but it is equally dangerous and offensive not to acknowledge the vulnerability of the children in those relationships.

Catton’s response is to leave that relationship in the background and only to discuss it through the prism of another person’s point of view: the girl’s parents and sister, her friends, the school’s counselling sessions, newspaper reports. By the end of the book, I’m no clearer as to that relationship: was he predatory, did she have a naive crush taken too far, was she a Lolita or was it just a stupid chaotic complicated human mess? We as the reader are excluded from that taboo relationship as completely as Victoria’s friends and family are. And as a result, we indulge in and share and are therefore complicit with the same rumour-mongering and gossip that the characters do.

It is also not the source of the novel’s sensuality: that comes through the writing and the relationships that surround the Saxophone Teacher and her pupils, especially Isolde and Julia. The language often lingers on tiny erotic details: the soft notched hollow of a collarbone, the down on her cheeks, glowing soft pink in the slanting light, the feathered lobe of an ear, a hand that snakes down the saxophone and trails around the edge of the bell. This sort of language pervades the book and, taken in isolation, looks perhaps a little too obvious, a little over-Freudian but within the context of the language of the book works brilliantly.

We are seduced by the beauty and poetry of the Saxophone Teacher’s language through this book. Her playfulness and sensuality and pleasure in her art and the artifices of others was deeply attractive. She, however, has her own agenda as well and, as she guides and moulds her students she becomes far more sinister than Mr Saladin did, reliving and voyeuristically or vicariously using the girls she taught to recreate her own relationships from the past. Her sensuality and language tempts and moulds us as readers and we simultaneously complicit in wanting her students to get together and are horrified by her machinations and sympathetic to her own needs and pain which she has suffered.

She is an extraordinary character.

Even more remarkably, Catton was a mere 22 years old when she wrote this as a debut novel. The heady, sensual self-discovery she describes had an authenticity that an older writer may not have achieved; but, to exhibit the control and self-awareness and sheer confidence we see here, in an author of that age, is exceptional.

[…] The Rehearsal by Eleanor […]

LikeLike

[…] the novel was strikingly experimental in style? Not really (compare Eleanor Catton’s novel The Rehearsal). Did I feel her use of language was lyrical and poetic? Again no (compare The History Of The Rain […]

LikeLike

[…] most memorable reads recently: Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, which led me to her wonderful The Rehearsal, Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale For The Time Being, How To Be Both by Ali Smith, Niall Williams’ […]

LikeLike

[…] I might offer up are either The Rehearsal, the debut novel by Eleanor Catton who won the Man Booker with The Luminaries, and Neil […]

LikeLike

[…] wonderful book – is Nicole Arumugam’s narration of Eleanor Catton’s debut novel, The Rehearsal who, I notice, having glanced at Wikipedia, is also […]

LikeLike

[…] each part with a starmap of which three are above. This was a book I loved with a passion, as I did The Rehearsal which was a vastly different novel, but felt that a huge amount went over my head in the erudition […]

LikeLike

[…] was fantastic, World War Z by Max Brooks worked very well with its multiple voices and, for me, The Rehearsal by Eleanor Catton was […]

LikeLike

[…] The Rehearsal […]

LikeLike

[…] The Rehearsal, Eleanor Catton […]

LikeLike

[…] The Rehearsal, Eleanor Catton […]

LikeLike

[…] Saxophone Teacher in The Rehearsal by Eleanor […]

LikeLike

[…] The Rehearsal, Eleanor Catton […]

LikeLike

[…] Saxophone Teacher, The Rehearsal, Eleanor […]

LikeLike

[…] head with all the astrology. I loved it so much I followed it up almost immediately with her debut The Rehearsal which blew me away as one of the most powerful, wonderful, hilarious, disturbing books I have every […]

LikeLike

[…] Catton has been one of my favourite authors since her debut The Rehearsal – her sense of voice in her writing is, in my opinion, exceptional, and the complexity and […]

LikeLike

[…] the novel blew me away. And prompted me to pick up her previous book – and debut – The Rehearsal. I adored her characterisation of the saxophone teacher and found her wonderful, compelling, tragic […]

LikeLike